|

تضامنًا مع حق الشعب الفلسطيني |

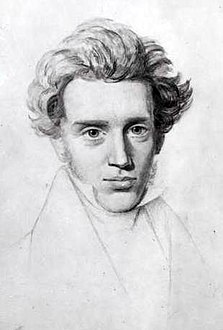

سورين كيركغور

| سورين كيركغور | |

|---|---|

| معلومات شخصية | |

| الميلاد | 5 مايو 1813 كوبنهاغن |

| الوفاة | 11 نوفمبر 1855 (42 سنة) كوبنهاغن |

| الديانة | مسيحية |

| الحياة العملية | |

| المدرسة الأم | جامعة كوبنهاغن، جامعة كوبنهاغن |

| التوقيع | |

| تعديل مصدري - تعديل | |

سورين كيركغور (باللغة الدنماركية:Søren Kierkegaard، ويُكتَب بالعربية أيضاً كيركيغارد أو كيركغارد أو كيركجارد أو كيركيجارد)؛ (5 مايو 1813م - 11 نوفمبر 1855م)،[1] سورين أباي كيركغور أو كيركغارد (5 مايو 1813- 11 نوفمبر 1855) هو فيلسوف دنماركي، ولاهوتي، وشاعر، وناقد اجتماعي، ومؤلف ديني، ويُعتبر على نطاق واسع أول فيلسوف وجودي.[2][3] كتب نصوصاً نقدية حول الدين المنظم، والمسيحية، والأخلاق، وعلم النفس، وفلسفة الدين، مظهرًا في ذلك حبًا للاستعارات والسخرية والأمثال. تتعامل الكثير من أعماله الفلسفية مع القضايا التي تناقش كيف يعيش المرء «كفرد منفرد»، مع إعطاء الأولوية للواقع الإنساني الملموس على التفكير المجرد وإبراز أهمية الاختيار الشخصي والالتزام.[4] كان ضد النقاد الأدبيين الذين حددوا المثقفين والفلاسفة المثاليين في عصره، واعتقد أن الباحثين فهموا هؤلاء الفلاسفة: سفيدنبوري،[5] وهيجل،[6] وفيشته، وشيلن، وشليجل بشكل أسرع من اللازم.[7]

يركز العمل اللاهوتي لكيركغور على الأخلاقيات المسيحية، ومؤسسة الكنيسة، والاختلافات بين البراهين الموضوعية البحتة للمسيحية، والتمييز النوعي اللانهائي بين الإنسان والله، وعلاقة الفرد الذاتية بيسوع المسيح[8] الإنسان-الإله التي تأتي عن طريق الإيمان.[9][10] يتعامل الكثير من أعماله مع الحب المسيحي. كان ينتقد بشدة تطبيق المسيحية كدين للدولة، وخاصةً ما تفعله كنيسة الدنمارك. استكشف عمله النفسي عواطف الأفراد ومشاعرهم عند مواجهتهم خيارات الحياة.[11]

كتب كيركغور أولى أعماله تحت أسماء مستعارة مختلفة استخدمها لتقديم وجهات نظر مميزة ولتتفاعل مع بعضها البعض في حوار معقد.[12] استكشف المشكلات المعقدة بشكل خاص من وجهات نظر مختلفة، كل منها تحت اسم مستعار مختلف. وكتب العديد من الخطابات التأسيسية باسمه الحقيقي وأهداها إلى «الفرد المنفرد» الذي قد يرغب في اكتشاف معنى أعماله. ومن أبرز ما كتب: «يريد العلم والبحث الدراسي تعليمنا أنّ الموضوعية هي الطريق. بينما تعلّم المسيحية أن الطريق الصحيح هو أن تكون ذاتيًا، أن تصبح فاعلًا.»[13][14] بينما يمكن للعلماء أن يتعلموا عن العالم من خلال الملاحظة، نفى كيركغور بشكل قاطع أن يكون للملاحظة قدرة على اكتشاف الأعمال الداخلية لعالم الروح.[15]

تشمل بعض الأفكار الأساسية لكيركغور مفهوم «الحقائق الذاتية والموضوعية»، وفارس الإيمان، وثنائية التذكر والتكرار، والقلق المشوب بالذنب، والتمييز النوعي اللانهائي، والإيمان كشغف، والمراحل الثلاث على طريق الحياة. كتب كيركغور باللغة الدنماركية وكان استقبال عمله يقتصر في البداية على الدول الاسكندنافية، ولكن مع بداية القرن العشرين، تُرجمت كتاباته إلى الفرنسية والألمانية وغيرها من اللغات الأوروبية الرئيسية الأخرى. وبحلول منتصف القرن العشرين، مارس فكره تأثيرًا كبيرًا على الفلسفة،[16] واللاهوت،[17] والثقافة الغربية.[18]

حياته المبكرة (1813-1836)

ولد كيركغور لعائلة ثرية في كوبنهاغن. عملت والدته «آن سورنسداتر لوند كيركغور» كخادمة في المنزل قبل الزواج من والده «مايكل بيدرسن كيركغور». كانت شخصية متواضعة، وهادئة، وبسيطة، وغير متعلمة رسمياً، لكن حفيدتها «هنرييت لوند»، كتبت أنها «مارست النفوذ بفرح وحمت سورين وبيتر مثل دجاجة تحمي فراخها».[19] كان لها تأثير على أطفالها، حتى أن بيتر قال في وقت لاحق أنّ شقيقه حافظ على الكثير من كلمات والدته في كتاباته. والده، من ناحية أخرى، كان تاجر صوف من يوتلاند.[20] قرأ كيركغور وهو شاب فلسفة كريستيان وولف. فضّل أيضًا كوميديا لودفيغ هولبيرغ، وكتابات جورج يوهان هامان، وغوثولد إفرايم ليسينج، وإدوارد يونغ، وأفلاطون، وخاصة تلك التي تشير إلى سقراط.[21]

منذ عام 1821 وحتى عام 1830، التحق كيركغور بمدرسة الفضيلة المدنية، حيث درس اللغة اللاتينية والتاريخ من بين مواد أخرى. وتابع في دراسة اللاهوت في جامعة كوبنهاغن. كان لديه القليل من الاهتمام بالأعمال التاريخية، ولم ترضه الفلسفة، ولم يتمكن من رؤية نفسه «مكرسًا للتخمين». قال: «ما أحتاج أن أقوم به فعلًا هو أن أكون واضحًا بشأن ماذا عليّ أن فعل، وليس ماذا يجب أن أعرف». أراد أن «يعيش حياة إنسانية كاملة وليس حياةً من المعرفة فحسب».[22] لم يكن كيركغور يريد أن يكون فيلسوفًا بالمعنى التقليدي أو الهيغلي، ولم يكن يريد التبشير بمسيحيةٍ وهمية. «لكنه تعلم من والده أنه يمكن للمرء أن يفعل ما يشاء، وحياة والده لم تنقض هذه النظرية».[23]

يومياته

وفقًا لصموئيل هوغو بيرجمان، «تُعد يوميات كيركغور واحدة من أهم المصادر اللازمة لفهم فلسفته».[24] كتب كيركغور أكثر من 7,000 صفحة في يومياته عن الأحداث، والتأملات، والأفكار حول أعماله وملاحظاته اليومية.[25] حُررت المجموعة الكاملة من اليوميات الدنماركية ونُشرت في 13 مجلداً مكونًا من 25 غلافًا منفصلًا بما في ذلك الفهارس. حرر النسخة الإنجليزية الأولى من اليوميات ألكساندر درو في عام 1938.[26]

أراد كيركغور أن تكون خطيبته «ريجين» صديقته المقربة، ولكنه اعتبر ذلك أمرًا مستحيل الحدوث، لذا ترك الأمر «للقارئ، ذلك الفرد المنفرد» ليصبح صديقه المقرب. كان يتساءل ما إذا أمكن للمرء أن يكون لديه صديق مقرب روحي. وكتب ما يلي في حاشيته الختامية:

«فيما يتعلق بالحقيقة الأساسية، فالعلاقة المباشرة بين الروح والروح أمر غير معقول. إذا افتُرض وجود علاقة كهذه، فهذا يعني في الواقع أن الطرف توقف عن كونه روحًا».[27]

كانت يوميات كيركغور مصدرًا للعديد من الأمثال والحكم المنسوبة إلى هذا الفيلسوف. المقطع التالي، العائد إلى 1 أغسطس عام 1835، هو ربما من أكثر أقواله استخدامًا وشكّل اقتباسًا رئيسيًا للدراسات الوجودية:

«ما أحتاجه حقًا هو أن أكون واضحًا بشأن ما يجب أن أفعله، وليس ما يجب أن أعرفه، إلا فيما يتعلق بالمعرفة التي تسبق كل فعل. ما يهم هو إيجاد غاية، لمعرفة ما الذي يريد مني الله حقًا أن أفعله؛ الشيء المهم هو العثور على الحقيقة التي هي حقيقة بالنسبة لي، لإيجاد الفكرة التي أنا على استعداد للعيش والموت من أجلها».[28]

ريجين أولسن وتخرجه

من أهم جوانب حياة كيركغور -والتي يُرَى أنها أثرت بشكل كبير على أعماله- خطبته المفسوخة مع ريجين أولسن (1822-1904). التقى كيركغور وأولسن في 8 مايو عام 1837 وانجذبا إلى بعضهما البعض على الفور، ولكن وفي وقت قريب من 11 أغسطس 1838 كان لكيركغور رأي آخر. وفي يومياته، كتب كيركغور بشكل مثالي عن حبه لها.[29]

في 8 سبتمبر 1840، تقدم كيركغور بطلب الزواج رسميًا من أولسن. ولكنه سرعان ما شعر بخيبة أمل من توقعاته. فسخ الخطوبة في 11 أغسطس 1841، رغم الاعتقاد العام بأن الاثنَين كانا غارقَين في الحب. في يومياته، أشار كيركغور إلى اعتقاده بأن «سوداويته» تجعله غير مناسب للزواج، ولكن يبقى دافعه المحدد لإنهاء الخطوبة غير واضح. في وقت لاحق، كتب كيركغور: «أنا مدين بكل شيء لحكمة رجل عجوز ولبساطة فتاة صغيرة.» ويُقال إن الرجل العجوز في هذا البيان هو والده والفتاة هي أولسن. قال عنه مارتن بوبر: «لم يتزوج كيركغور في تحدٍ منه للقرن التاسع عشر بأكمله». قال الجميع إنه من واجب كل شخص أن يتزوج، ولكن كيركغور عارض ذلك.[30][31][32]

حوّل كيركغور انتباهه إلى امتحاناته. في 29 سبتمبر 1841، قدم كيركغور أطروحته ودافع عنها: حول مفهوم المفارقة مع الإشارة المستمرة إلى سقراط. رأت لجنة الجامعة أطروحته جديرة بالملاحظة ومدروسة، ولكن غير رسمية، وفكاهية بالنسبة لأطروحة أكاديمية جادة. تناولت الأطروحة السخرية ومحاضرات شيلن لعام 1841، والتي حضرها كيركغور مع ميخائيل باكوني، وجاكوب بوركهارت، وفريدريك إنجلز؛ وأخذ لاحقًا كل واحد منهم منظورًا مختلفًا.[33]

تخرج كيركغور من الجامعة في 20 أكتوبر 1841 مع ماجستير في الآداب. كان قادرًا على تمويل تعليمه ومعيشته وعدة منشورات من أولى أعماله بواسطة ميراث أسرته البالغ نحو 31,000 ريغسدالر (عملة الدنمارك في ذلك الوقت).[26]

انظر أيضًا

مراجع

- ^ سورين كيركغور على موسوعة بريتانيكا

- ^ Swenson, David F. Something About Kierkegaard, Mercer University Press, 2000.

- ^ Kierkegaard، Søren (1849)، "A New View of the Relation Pastor–Poet in the Sphere of Religion"، JP VI 6521 Pap. X2 A 157،

Christianity has of course known very well what it wanted. It wants to be proclaimed by witnesses—that is, by persons who proclaim the teaching and also existentially express it. The modern notion of a pastor as it is now is a complete misunderstanding. Since pastors also presumably should express the essentially Christian, they have quite rightly discovered how to relax the requirement, abolish the ideal. What is to be done now? Yes, now we must prepare for another tactical advance. First a detachment of poets; almost sinking under the demands of the ideal, with the glow of a certain unhappy love they set forth the ideal. Present-day pastors may now take second rank. These religious poets must have the particular ability to do the kind of writing that helps people out into the current. When this has happened, when a generation has grown up that from childhood on has received the pathos-filled impression of an existential expression of the ideal, the monastery and the genuine witnesses of the truth will both come again. This is how far behind the cause of Christianity is in our time. The first and foremost task is to create pathos, with the superiority of intelligence, imagination, penetration, and wit to guarantee pathos for the existential, which 'the understanding' has reduced to the ludicrous.

. - ^ Gardiner 1969

- ^ Emanuel, Swedenborg The Soul, or Rational Psychology translated by Tafel, J. F. I. 1796–1863, also see Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, Hong trans., p. 332ff (The Thorn in the Flesh) (arrogance) نسخة محفوظة 21 يونيو 2019 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- ^ Søren Kierkegaard 1846, Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, Hong p. 310-311

- ^ Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, A Mimical-Pathetic-Dialectical Compilation an Existential Contribution Volume I, by Johannes Climacus, edited by Soren Kierkegaard, Copyright 28 February 1846 – Edited and Translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong 1992 Princeton University Press p. 9-10

- ^ Point of View by Lowrie, p. 41, Practice in Christianity, Hong trans., 1991, Chapter VI, p. 233ff, Søren Kierkegaard 1847 Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, Hong p. 225-226, Works of Love IIIA, p. 91ff

- ^ Duncan 1976

- ^ Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, Hong trans., pp. 15–17, 555–610 Either/Or Vol II, pp. 14, 58, 216–217, 250 Hong

- ^ Ostenfeld & McKinnon 1972

- ^ Howland 2006

- ^ Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, 1847 Hong 1995 p. 283

- ^ Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Hong trans., 1992, p. 131

- ^ Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Postscript both deal with the impossibility of an objectively demonstrated Christianity, also Repetition, Lowrie 1941 p 114-115, Hong p. 207-211

- ^ Stewart, Jon (ed.) Kierkegaard's Influence on Philosophy, Volume 11, Tomes I–III. Ashgate, 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Jon (ed.) Kierkegaard's Influence on Theology, Volume 10, Tomes I–III. Ashgate, 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Jon (ed.) Kierkegaard's Influence on Literature and Criticism, Social Science, and Social-Political Thought, Volumes 12–14. Ashgate, 2012.

- ^ Glimpses and Impressions of Kierkegaard, Thomas Henry Croxall, James Nisbet & Co 1959 p. 51 The quote came from Henriette Lund's Recollections of Søren Kierkegaard written in 1876 and published in 1909 Søren was her uncle. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001396450 نسخة محفوظة 2020-04-26 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- ^ Bukdahl، Jorgen (2009). Soren Kierkegaard and the Common Man. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ص. 46. ISBN:9781606084663.

- ^ Johannes Climacus by Søren Kierkegaard, p. 17

- ^ The Point of View of My Work as An Author: A Report to History by Søren Kierkegaard, written in 1848, published in 1859 by his brother Peter Kierkegaard Translated with introduction and notes by Walter Lowrie, 1962, Harper Torchbooks, pp. 48–49

- ^ Hohlenberg، Johannes (1954). Søren Kierkegaard. Translated by T.H. Croxall. Pantheon Books. OCLC:53008941. مؤرشف من الأصل في 2020-02-01.

- ^ Hugo Bergmann Dialogical Philosophy from Kierkegaard to Buber p. 2 نسخة محفوظة 2 أبريل 2017 على موقع واي باك مشين.

- ^ Given the importance of the journals, references in the form of (Journals, XYZ) are referenced from Dru's 1938 Journals. When known, the exact date is given; otherwise, month and year, or just year is given.

- ^ أ ب Dru 1938

- ^ Concluding Postscript, Hong trans., p. 247

- ^ Dru 1938، صفحة 354

- ^ Garff 2005

- ^ Gabriel، Merigala (2010). Subjectivity and Religious Truth in the Philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ص. 9. ISBN:9780881461701.

- ^ The Christianity of us men is, to love God in agreement with other men, to love and be loved by other men, constantly the others, the herd included. The Christianity of the New Testament would be: in case that man were really able to love in such a way that the girl was the only one he loved and one whom he loved with the whole passion of a soul (yet such men as this are no longer to be found), then hating himself and the loved one, to let her go in order to love God.-And it is in view of this I say that such men, men of such quality and caliber, are not born any more. Kierkegaard’s Attack Upon "Christendom" Lowrie 1944 p. 163

- ^ See Stages on Life's Way, Hong trans., p. 195ff and 423ff Here he wrote about his conflict with his own guilt. Stages, p. 380-382 Am I guilty, then? Yes. How? By my having begun what I could not carry out. How do you understand it now? Now I understand more clearly why it was impossible for me. What then is my guilt? That I did not understand it sooner. What is your responsibility? Every possible consequence of her life. Why every possible one, for this certainly seems to be exaggeration? Because here it is not a matter of an event but of an act and an ethical responsibility, the consequence of which I do not dare to arm against by being courageous, for courage in this case means opening oneself to them. What can serve as your excuse? ...

Think of the first word and the hyphen of a compound word, and now suppose that you do not know any more about how it hangs together-what will you say then? You will say that the word is not finished, something is lacking. It is the same with the one who loves. That the relationship came to a break cannot be directly seen; it can be known only in the sense of the past. But the one who loves does not want to know the past, because he abides, and to abide is in the direction of the future. Therefore, the one who loves expresses that the relationship, which the other call a break, is a relationship that has not yet finished. But it is still not a break because something is missing. Therefore, it depends on how the relationship is viewed, and the one who loves-abides. So it came to a break. It was a quarrel that separated the two; yet one of them made the break, saying, "It is all finished between us." But the one who loves abides, saying, "It is not all finished between us; we are still in the middle of the sentence; it is only the sentence that is not finished." Is this not the way it is? What is the difference between a fragment and an unfinished sentence? In order to call something a fragment, one must know that nothing more is coming; If one does not know this, one says that the sentence is not yet finished. When from the angle of the past it is settled that there is no more to come, we say, "It is a fragment"; from the angle of the future, waiting for the next part, we say, "The sentence is not finished; something is still missing." …. Get rid of the past, drown it in the oblivion of eternity by abiding in love-then the end is the beginning, and there is no break! Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, Hong 1995 p. 305-307

- ^ Journals & Papers of Søren Kierkegaard IIA 11 13 May 1839

روابط خارجية

| سورين كيركغور في المشاريع الشقيقة: | |

- مقالات تستعمل روابط فنية بلا صلة مع ويكي بيانات

- مواليد 1813

- وفيات 1855

- وفيات بعمر 42

- سورين كيركغور

- أخلاقيون مسيحيون

- أسماء قلمية

- أشخاص من كوبنهاغن

- أنطولوجيون

- إنسانويون مسيحيون

- بروتستانت دنماركيون

- تاريخ الأديان

- تاريخ الأفكار

- تاريخ الفلسفة

- تاريخ أخلاقيات

- تاريخ علم النفس

- خريجو جامعة كوبنهاغن

- روائيون دنماركيون

- روائيون دنماركيون في القرن 19

- روائيون مسيحيون

- شخصيات مقدسة في التقويم اللوثري الطقوسي

- شعراء دنماركيون

- شعراء دنماركيون في القرن 19

- شعراء لوثريون

- شعراء مسيحيون

- فلاسفة الأدب

- فلاسفة الأديان

- فلاسفة الثقافة

- فلاسفة الحب

- فلاسفة العقل

- فلاسفة القرن 19

- فلاسفة الموت

- فلاسفة أخلاق

- فلاسفة بروتستانت

- فلاسفة دنماركيون

- فلاسفة دنماركيون في القرن 19

- فلاسفة علم الاجتماع

- فلاسفة قاريون

- فلاسفة لوثريون

- فلاسفة من الفن

- فلاسفة من علم النفس

- فلاسفة نظرية المعرفة

- قديسون أنجليكانيون

- كتاب دنماركيون

- كتاب دنماركيون في القرن 19

- كتاب غير روائيين ذكور دنماركيون

- كتاب في القرن 19

- كتاب مقالات دنماركيون

- كتاب مقالات في القرن 19

- كتاب من كوبنهاغن

- كتاب يوميات دنماركيون

- كتاب يوميات في القرن 19

- كتب فلسفية

- لاهوتيون بروتستانت في القرن 19

- معلقون اجتماعيون

- منظرو السخرية

- مواليد في كوبنهاغن

- ميتافيزيقيون

- نقاد اجتماعيون

- نقاد ثقافيون

- نقد أدبي دنماركي

- وجوديون

- وجوديون مسيحيون

- وفيات السل في الدنمارك

- وفيات بسبب السل في القرن 19

- وفيات في كوبنهاغن

- كتاب بأسماء مستعارة القرن 19